I met Cathrine viaSun Mingrui who has been classmate to Cathrine at the National Academy of Artsin Oslo. I was interested when I heard that there was girl whoes graduationwork was related to her Chinese family. Norway is a very small place, where anything with China would catch myattention. So a few months later, Cathrine and I met at a cafe near Løren inOslo. We talked about her graduation work for about two hours. If I would use asentence to describe my feelings, it is: I am surprised by her retrospectionand thinking of her Chinese background. I have had some contact with the second generation of Chinese born inNorway. Most of their understanding of Chinese culture is limited andstereotyped. They definitely know some Chinese culture symbol such as antitheticalcouplet, but no more than that. When they grow up, they vanish among ordinaryNorwegians. That is why I was surprised and interested by her work. So, who isCathrine Liberg and what is her work about?

1. Could you give us a shortintroduction of yourself?

My name is Cathrine Alice Liberg. I was born andraised in Norway to a Norwegian father and a Chinese-Singaporean mother. Irecently graduated with a Masters degree from the Oslo National Academy of theArts (KHiO), and am now working as an artist and printmaker.

In my artistic practice, I am interested in theChinese diaspora. How do Chinese migrants across the world remember theirhomeland, and how are these memories passed down to their children who grow upin new countries?

2. What isyour master’s project about?

In my master’s project, I tried to create imaginary photographs of myChinese great-grandmother, of whom we have no photographs or records of. We donot even know her name. All I know is that she was born in Guangdong in thebeginning of the 1900s, and later moved to Singapore to live as mygreat-grandfather’s concubine. Here she gave birth to six children before dyingin poverty at the age of 33.

As a child, growing up in Norway, my great-grandmother was always a verymythological figure to me. I imagined her as the many tragic concubines I hadseen in Chinese films. Perhaps she was like Li Gong in Zhang Yimou’s “Raise theRed Lantern”, who was driven mad by her circumstances? Or perhaps she was likeAn Mei’s mother in Amy Tan’s “The Joy Luck Club” who killed herself with opium?There never seems to be happy endings for concubines in Chinese stories.

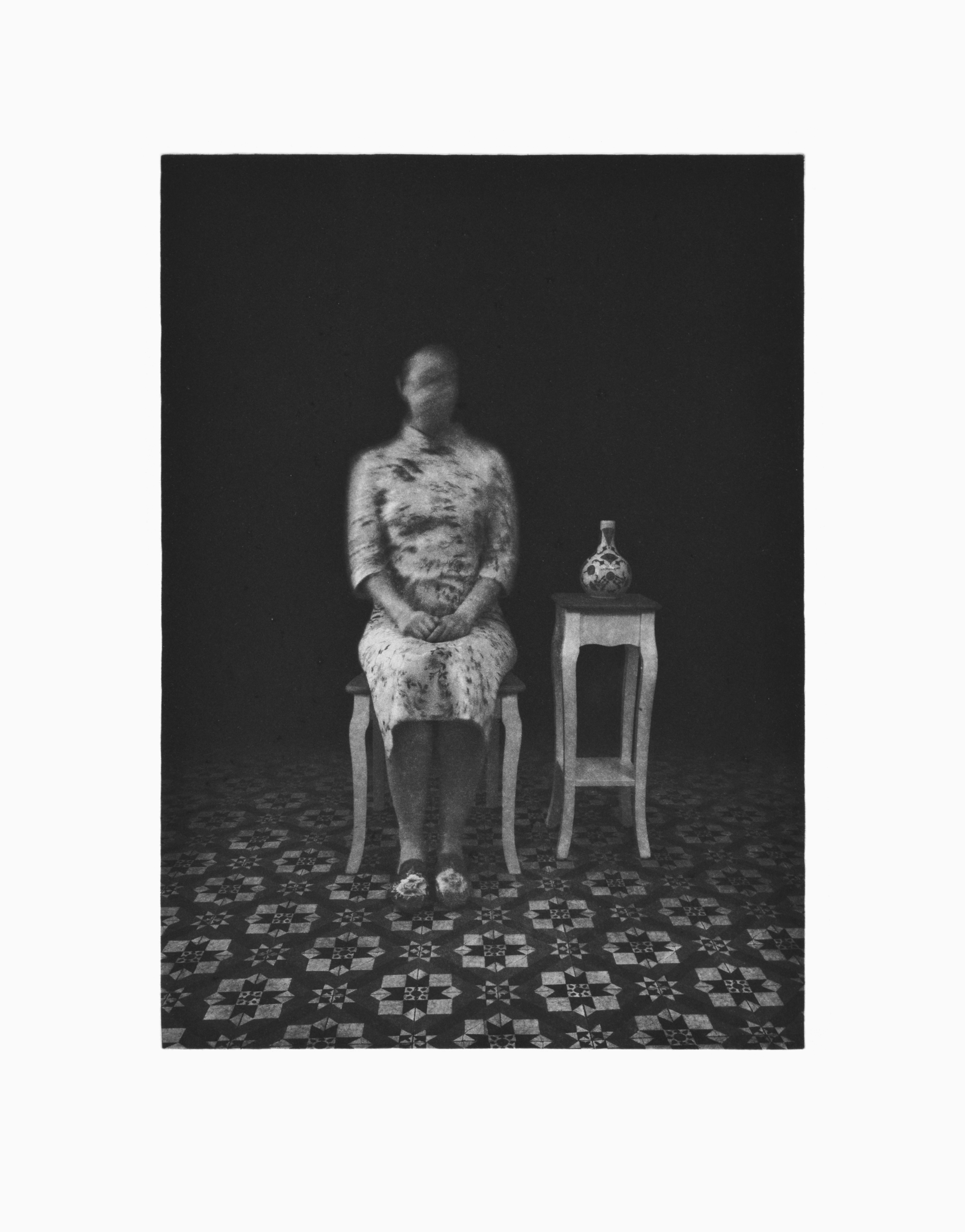

In order to create photographs of my Chinese great-grandmother, Idecided to dress up as her myself. There is still something of her in megenetically, and perhaps through the transformational qualities of the camera,I could turn myself into her and somehow house her spirit. She died only acouple of years older than I am now, so to me it felt important to do theproject before I became too old to portray her.

I wanted to capture her throughout the various stages of her life – fromher humble beginnings in China, to her life as a wealthy concubine and a motherin Singapore, and in the end as a woman who died in desperate poverty. Whenstaging these images, I had to rely on both fantasy and historical research inorder to re-construct a past that had been lost to us. I dressed up in clothesI could imagine her wearing, from simple cotton qipaos, to silk robes and thetraditional “Sarong Kebaya”, which is one of the national costumes of Singaporeand Malaysia. Using fabrics and patterned paper, I made the interior of myapartment resemble the backdrops of traditional Chinese ancestor portraits andearly Chinese studio photographs. In the lack of authentic Chinese furniture, Iposed with Chinese-inspired furniture found at a local home decor store. On thesmall table I placed a variety of Chinese and South-East Asian decorativeitems, some which I had purchased during my travels to Asia, and some which Ihad made myself – for example a series of porcelain vases.

The composition, in which I am seated and seen from a full-frontal view,is very much based on the visual traditions of Chinese ancestor portraiture andearly Chinese portrait photography. This composition differs greatly from earlyWestern photography, in which the sitter is often seen posing in athree-quarter view and looking more relaxed and informal. The images wereexhibited as a series of seven portraits in one long frame, showing the storyof my great-grandmother in a chronological order. The last image is of me inmodern day clothing where I portray myself reflecting back on the other imagesand the story I have told.

3. Tell us something about of yourfamily history?

My Chinese great-grandmother came from humbledwellings in Nanhai, a district in Guangdong. Here she had most likely beenspotted by my great-grandfather, a wealthy businessman from Hong Kong whowished to take her for his concubine. Apparently, it was common to look forpretty young girls in the poorer districts outside the affluent British colony.A wife you took for her dowry and status – a concubine for her youth andbeauty.

Sometime in the 1920s, they moved to Singapore. I’veconcluded that my great-grandmother must have lived comfortably at some point,because my great-grandfather had owned a big rubber plantation on the smallSouth-East Asian island, and could afford to take a wife and two concubines –my great-grandmother being the second of his three consorts. I am ashamed tosay that I have often judged her, finding it incomprehensible that a woman, andmy own relative at that, should stoop to what I deem to be such a degradingposition. A second wife, or concubine, held a very inferior position to thefirst wife, to whom she and her children had to submit themselves at all times.Considering my great-grandmother’s limited prospects however, it is perhaps notsurprising that she should have made this move – whether by her own choice, orthat of her family’s. Polygamy was socially accepted under the pretext of needingto perpetuate the male line.

My great-grandmother gave birth to six children duringher twenties. One baby died in a tragic accident, and a seventh was lost inmiscarriage. Misfortune struck again when my great-grandfather suffered astroke and lost all his money and his estates. The consequence must have beendire poverty, as his third consort left him and my own great-grandmother,having nowhere to go with five children, died from malnutrition and sheerexhaustion at the young age of thirty-three. Her husband passed away shortlyafter. At his funeral, all of her children, including my grandmother, had toremain outside the temple, as they were only the offspring of a concubine. Thisis something my grandmother never forgot, and told me repeatedly throughout mychildhood.

Orphaned and with four younger siblings to take careof, my grandmother sought refuge in a catholic convent run by British nuns.There she lived in safety, until the Japanese invaded Singapore in 1942. Shewas only a teenager when she had to flee to the jungle and go into hiding. Shenever received a formal education – instead she had to rely on her cunning andwits in order to keep the family alive. Apparently, she used to smuggle illegalgoods over the border to Malaysia. She was the toughest lady I have ever known.After the war, she married and had four children. When her husband, mygrandfather, died only a few years later, she married a British sailor. Itwasn’t really a love match, but he had fallen hopelessly in love with her, andshe saw it as a means to escape the hardships she had endured. After Singaporegained its independence and the British forces had to retreat from the island,the whole family moved t

o the UK in the late 1960s.

My mother later moved to Norway. Growing up here, Iobserved my mother’s and grandmother’s longing for their Chinese culture. Ithink many Chinese families across the globe are bound together by thecollective myth of China. While China still physically exists, it is somethingwhich first and foremost remains in the mind, locked in the time in which itwas left behind. It is no longer a conventional, physical home, but one that isemotional and psychological. The desire to return is not only a desire toreturn to a place, but to go back to a time in which you lived in this place.For example, my Chinese family (and many other Chinese families in Singapore)left China long before the communist revolution, so I think their version ofChinese culture and their idea of China is very different from what mainlandChina is actually like. Same happened later when my family left Singapore andmoved to the UK. I think they still have a very nostalgic view of Singapore,and their idea of it is locked in a time capsule going 50 years back.

4. How did you come up with this idea?

Ithad always been a great source of sadness to me that I had never been able tofind any photos of my Chinese great-grandmother. I was very curious as to whatshe had looked like. Then one day, I came across a book about traditional Chineseancestor portraits. Here I learnt that ancestor portraits were often paintedposthumously (that is, after a person’s death), and that the painter sometimesstudied the facial features of living relatives in order to reconstruct theface of the deceased. This book gave me the idea of how I could make my ownimages of my great-grandmother by combining the faces of her descendants. Ibegan layering the faces of myself, my mother and my grandmother on top of eachother using Photoshop in order to combine our features. The intention was tosomehow work my way backwards through the generations, revert the geneticheritage and reconstruct the lost face of our common ancestor. This projectlater evolved into my master’s project, where I dressed up as my great-grandmotherin order to try and “become” her.

5. Whatdo you want to present to us and why? Is it more of a personal expressing or isit something that associated with society?

Although these projects are quite personal, I feelthat they represent more than just my family history. These images are verymuch a symbol of how I, as a contemporary artist in Europe, am trying to createa version of a Chinese past without actually knowing China. My images are verymuch influenced by stereotypical characters from movies and books. The costumesI am wearing I got from Amazon. The furniture in the images are not Chinesefurniture – but European furniture made by Europeans to look “Chinese”. I wasvery conscious about wanting to incorporate these elements in my work, to showhow I, and many children of immigrant parents, have a view of our parents’homeland that can be quite distorted. I want to question how we both interpretand misinterpret our parents’ culture. I hope, and believe, many can recognizethe longing to reconstruct and understand the past. At the same time, I thinkit is important to remember that we often resort to stereotypes in order to doso.

6. We are surprised by your curiosity ofyour Chinese background and family history, which is very typical Chinese mentality.Is there anything or anyone inspiring you on this?

Even though she spent the last fifty years of her life in the UK, mygrandma never forgot Singapore or her Chinese culture. She would often say tome: “I miss my culture, Cathrine”. She told my mum that it was very importantthat she came to Norway at least once a year to see me. “How else will she knowthat she has a Chinese grandmother?” she used to say. She passed away almostexactly two years ago, at the age of 90. I loved her immensely, and she hasbeen a massive influence in my life, my personality and outlook. I believe itwas very important for her that the grandchildren retained some aspects ofChinese culture – or at least became familiar with it. Also, because I lived sofar away from her and saw her so seldom, I think I treasured her stories andmemories more highly than my cousins did.

7. China has been through huge changesin the last century, the image of China that exists in some overseas Chinesemay be quite different than what China is now. So the question is, what is yourgeneral image of China?

I think both my mum and I were very surprised thefirst time we travelled to mainland China back in 2006. For much of the 20thcentury, there weren’t many news coming out from the mainland, so we really didnot know what to expect. We were amazed at how fast it had developed – I hadnever experienced a city as futuristic as Shanghai. I think we still have a bitof a romanticized view of China though. We watch quite a few Chinese tv-seriesand movies, which are all set in ancient dynasties, such as the Tang dynasty.That is the China we get through our television screens on a daily basis – notthe modern China of today. That being said, we enjoy experiencing both.

8. Do you think you have a differentemotional feeling toward China than the other ordinary Norwegian people? (Iwill give you an example, once I went to see a Chinese documentary about onechild policy in China, there was some heart-broken episode which was presentedin an amusing way, andmost Norwegian just burst into laughs, but I just cannot, for them, it issomething that is so far away, and so foreign, but for me, I feel it isconnected with me, what would you feel? Maybe it is too personal?)

I probably do, although I find myself often swappingbetween a Norwegian and Chinese viewpoint on things, and will thereforesometimes be surprised by my reactions. Sometimes I will laugh at jokes aboutChinese culture, while sometimes I will feel very personally hurt and offended.I also think I have a less black-and-white view. Western media is often very criticalof China – however when you look back at China’s history, you can sometimes understandwhy things are the way they are. We do not learn anything about Asian historyin Norwegian schools, so I think it is hard for many Norwegians to understandthe socio-political aspects of the region. My view is often a bit more nuancedbecause I have read a lot about Chinese history.

9. Have read any books or movies that isabout China? What are they?

As a teenager I read “Wild Swans” by Jung Chang, whichprofoundly moved me. It has also been a great inspiration to me, because ittells a bigger story of China through the personal viewpoint of just onefamily. I also read the novel “The Joy Luck Club” by the Chinese-Americanauthor Amy Tan. It tells about the cultural conflicts that arise between fourChinese mothers and their American-born daughters. I always recognize myself init.

10.Will you keepdiscovering the Chinese culture in the future?

I think what I am most interested in researching nextis how Chinese culture has evolved differently between the mainland, Taiwan,Singapore, Hong Kong, the UK, the US etc. Because my own Chinese family isscattered around the globe, I am interested in how Chinese culture blends withlocal cultures all across the world.

11. Will you pass your attachment withChina to your next generation?

I will, but it will be a version of Chinese culturethat is very much merged with Norwegian and English traditions. It will be oneof the many global variants of Chinese culture.

List of images in the below, chronological order